Introduction:

Porcelain paving, also known as ceramic or vitrified paving, is the latest buzzword for the hard-landscaping industry and many in the trade think it could well become a significant format, taking as much as 20% of market share, in the years ahead.

It's been popular in what we might think of as Southern Europe for many years, particularly Italy and Spain, which largely stems from their long tradition of producing and using ceramic (porcelain) tiles throughout the house. Egad! They even use tiles in places other than the kitchen and bathroom! Whatever next?

So, while more and more of us will be specifying and installing porcelain paving, it's probably a good idea to look at just how these 'tiles' are actually manufactured, which is why pavingexpert.com blagged itself an invite to one of the leading factories in northern Italy, accompanying leading importer, Rock Unique, on one of their fact-checking missions.

When describing the techniques and machinery in what follows, the aim has been to keep it as generic and non-specific as possible. Obviously, some of this is done to protect the commercial interests of the manufacturer in question, but there is also a need to keep the description reasonably vague because different manufacturers will tweak the precise principles and the ingredients to produce what they believe to be the most suitable product, in much the same way that a chef tweaks their recipe for, say, a steak and ale pie. It's still a steak and ale pie, but some are tastier than others!

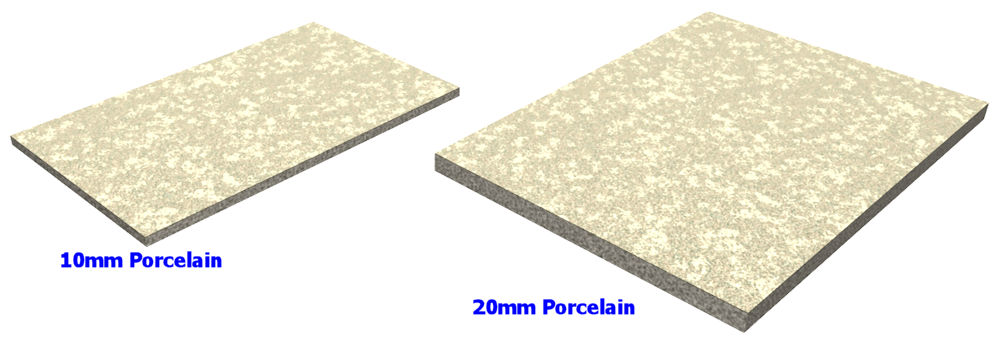

Thickness:

Amongst several of the better quality European porcelain paving manufacturers, there is a loose agreement that porcelain for outdoor use is best manufactured as a 20mm thick unit. Some European manufacturers, and many of those in Asia, manufacture 10mm thick units and this is not necessarily a 'bad thing'. Porcelain is unbelievably tough stuff and, given a quality-controlled and thorough manufacturing process, it's possible to make a case for 10mm thick paving, especially for the smaller elements (less than 600x600mm in plan). However, 20mm thick seems to be the preference in Europe, and that is certainly the case for the factory visited prior to developing this page.

Manufacturing:

Porcelain is manufactured from a blend of clays, sands and other minerals which are then baked in a high-temperature kiln. There is a lot of preparation required before the unbaked 'biscuit' can be sent into the kiln, and then there's a fair bit of post-firing work required to ensure that what is sent out to the trade is of a sufficient quality and standard. What follows gives a brief summary of each of these key stages of manufacture.

The ingredients:

The Italian factory visited as part of the research for this page uses four key ingredients (plus water) to create the base mixture for porcelain:

- High quality fine clays sourced locally, and from Turkey and Germany

- Quartzitic sand – very pure, fine sand from Germany

- Feldspar – a granitic mineral from various sources

- Kaolin – known as China Clay in Britain and Ireland, this is another by-product of granite weathering and is typically sourced from the Ukraine.

Preparation:

Specific quantities of these dry aggregates are mixed together with clean, cold water into a slurry which is then processed in a ball mill to reduce the aggregates to very fine particles, so fine the resulting slurry seems like a slippery mud, with no discernible grittiness. Rub it between your fingers and it will slide like a lubricant, almost, leaving a streak across the skin.

Drying:

As a slurry, the mix of aggregates is very easy to move around the factory, but most of the water content has to be removed before the mix can be used further. This is done in a screen drier which uses hot air and gentle rotation to reduce the moisture level to just 6% (or thereabouts). The recovered water can be re-used to create a new slurry, so losses are kept to a minimum.

Mix storage:

The dry-ish powder is now stored in a silo until it is required. Different mixes are stored in separate silos, and there can be as many as 80 silos, each holding a slightly different mix, with more or less clay, say, or a higher proportion of kaolin.

The Techno-tower:

Despite the name, this is not some hare-brained invention from the cellar of Wallace and Grommit's house, but a state-of-the-art blending machine, which prepares the actual porcelain material. Each tower (and there can be several in a factory) takes precise quantities of particular mixes from various silos and creates a blend specific to the product being manufactured. A darker coloured porcelain, for example, might have more content from, say, silo 23 and less from silo 35, while a pale porcelain might use more from silo 8 and none at all from silo 17.

The key to producing quality porcelain lies in blending the perfect quantities of various mixes to create the ideal biscuit ready to be baked.

Pressing:

The blended powder emerging from the Techno-Tower is then pressed into moulds. Some moulds will be smooth, with no surface relief; others will have profiled surfaces, or specific textures. Some will be square, some will be rectangular. Some will be small, say 300x300mm, and some will be bloody humungous (this factory is capable of producing a 2400x1200mm mega-tile!)

The blended powder is subjected to enormous pressure, compacting it into the chosen mould, so much so that it is reasonably hard, like a crumbly Digestive biscuit, even before it is fired in the kiln.

Final Drying:

After pressing, the moisture content of the 'biscuit' (which, you will recall, is about 6%) is reduced even further, to just 1-1.5%, by passing it through another drier, again recovering the water for re-use.

The biscuit which emerges from this process is noticeably harder, crisper, tougher, more like a Morning Coffee, requiring that bit more of an effort to snap it in the hand.

Printing and colouring:

Many porcelain tiles, and paving is no exception, have a pattern or image printed onto the surface to give the appearance of, say, travertine, fancy marble or even aged timber, amongst many others.

The surface of the biscuit may well be washed, dried, treated with various chemicals to enhance glazing or patterning, or to improve its finished appearance and/or performance,

Highly specialised inks, toners, colourants and pigments are used in the patterning process. When the pieces emerge fresh from the printing stage, it may seem that nothing at all has been done to them, the tiles looking almost exactly the same as they did before passing through the various machines. Often, the true colour and appearance will only become evident once the pieces have been fired.

Different manufacturers will use different techniques to produce the image/pattern, but two of the more common techniques are:

Roller printing:

The pattern is contained on a roller under which each tile passes and the pattern is effectively inked onto the surface of the tile. On some of the higher quality products, there will be some 'offset' of the patterning, vertically and horizontally, to produce variation in the finished appearance and ensure (hopefully) that there is no obvious repetition from piece to piece.

Inkjet printing:

Yes: Inkjet printing, not too dissimilar to that machine parked next to your own computer.

The desired image or pattern is, in essence, printed onto the surface of each piece. Obviously, the ink is not the sort of stuff you can get at a discounted price from Cartridges-R-Us, but are specially created pigments that will bond with the porcelain mix and only full reveal themselves after the tiles have been through the kiln.

However, the principle is exactly the same. An image or pattern, usually a high resolution photographic image, is loaded into the system and a selected portion of that is printed by squirting microscopic drops of pigment onto each piece as it passes through.

For some items, complex patterns and effects are achieved by combining the roller technology with inkjetting. This can create incredibly ornate and naturalistic patterning that can be almost indistinguishable from the 'original' surface from which the pattern was taken.

Firing:

All the preparation is now done. The porcelain biscuits are pressed, relief moulded, printed, pre-treated, and ready for for the kiln. The links of the ever-turning conveyor system now change to a heat-resistant format and carry the biscuits into the fierce heat of a kiln that can stretch for 100 metres or so.

As the pieces progress through the kiln, the temperature is very finely controlled, with a gradual increase, initially, reaching a peak of around 1,200°C before going through an equally finely-controlled cooling stage. The cooling is just as important and the heating in producing a quality tile.

The precise size, shape, thickness and material blend of the pieces play a role in determining the perfect firing profile. Some will need to be heated up more quickly; some will be maintained at maximum temperature for a longer period; others will have slower cool-off stage, and it is the skill of the manufacturer, along with the very expensive technology embedded in the kiln itself, which ensures each and every item passing through the furnace emerges in as good a condition as is possible.

The new kilns in this factory are only a year or so old, and the plant managers assure us that it is this constant re-investment on the very latest and very best equipment that enables them to maintain their position as a leading manufacturer, shipping porcelain tiles and paving all over the world. In each year, they expect to re-invest 10-15% of turnover into research and development, as this is the only way they can be sure of maintaining market share. It certainly engenders confidence in their products!

Despite the state-of-the-art insulation, and the very latest heat-conservation technology, the scorching heat of the kilns is palpable as you take the long walk between them to the delivery end, where the porcelain products, now cooled to a mere 100°C or so, and with the colouring and patterning now fully evident, emerge to be passed on the the post-firing processes.

Sizing:

One aspect of porcelain production that may not be immediately obvious to anyone not familiar with the technology is just how much shrinkage takes place during firing. Just how much an individual piece will shrink depends on the starting size, obviously, and also the shape. As a very rough-and-ready indication of the amount of shrinkage, a piece intended to be 600x600mm when finished, may well enter the kiln measuring 720x720mm, and emerge measuring only 605x605mm.

There is money to be lost in producing pieces which are grossly oversize. Not only does that mean more wastage of precious materials, but there are the costs of firing all that additional porcelain, not too mention the high costs of grinding down all that surplus porcelain until the precise size is achieved, which is the main subject of this section.

Each piece progresses through a series of diamond-tipped grinding sets (one grinding wheel to each side) which gradually reduce the tile to the desired size, the tile being rotated through 90° so that all four sides are trimmed. The grinding sets become progressively finer so that an exact, and smooth, edge finish is achieved.

Unsurprisingly, this extremely noisy (and dirty, despite the dust suppression) process is all done within an enclosure, so that the surprisingly few operatives and quality control managers on the factory floor are not exposed to any significant risk.

Additional treatments:

Certain products, but typically not paving, may well be subjected to additional treatments, either before or after sizing. These might include honing to produce an ultra-smooth surface, or application of a sealant, wax or protective coating. The range of options is extensive, and each treatment will have its own application procedure, but there are far too many to detail here.

Checking:

Most of the physical work in this factory is undertaken by robots. A small bunch of quality managers sit in a protective booth, monitoring computer screens, and an even smaller bunch of machine inspectors make physical tweaks and adjustments as required, notably to the roller printing stage, but almost everything else is done by robots.

When a mould is filled with the prepared powder and then pressed into shape, it's easy to think that's done by a machine, but it is, to be accurate, a robot. However, the giant transporters which float across pre-determined paths on the factory floor, carrying finished pieces to the correct checking machinery and from there to the packaging area are, without any doubt, robots. These driverless stackers hover, it seems, as they slowly and almost silently sweep from stage to stage, moving completed items from the sizing enclosure to the colour and shade checking station, and from there to other parts of the plant. Impressive!

The checking is viewed as a vital part of controlling quality. The plant managers report that, once, this was a job for nimble handed and sharp-eyed ladies, but nowadays, almost inevitably, it's done by robots and photo-electric cells. The firing process can have a variable effect on the finished colour of the tiles. The aim is, of course, to have a high degree of consistency, each and every piece within a batch achieving precisely the desired colour and shade, but because of the tiny differences in and along the length of the kiln, there can be minor variation, in some cases so slight that it's barely perceptible to the human eye. But the robot eyes see everything!

As each unit passes beneath the scanning robotic eye, its shade is checked against a reference piece. If the shade is assessed to be spot on, it is assigned the shade code 50. If it's a touch lighter than the reference piece, it may be labelled as shade code 48. Lighter still and it will be 46 or even 44. However, if it's a tad darker than the reference sample, it could be shade code 52; darker still and it might be 54, 56 and so on. The further away from the central value of 50 is the shade code, the lighter or darker it is than the ideal.

When laying large areas of porcelain tiles or paving, it's good practice to ensure the shade codes are all the same.

Luckily for us, this particular factory has an ingenious system whereby the robot handlers plucks out all the '50' pieces, and places them together in a single pack, labelling the whole pack as shade code 50. Similarly, all the 48s, all the 52s, etc., are all placed into boxes containing the same shade.

So, rather than having to check individual pieces, as long as the units are all taken from the same pack, and that the other packs being used all have the same shade code, there should be no problem. Note that the shade code doesn't have to be all 50s. The packs being used could be all 48s, or all 54s – as long as all the pieces being used have the same shade code, the finished effect will be acceptably uniform, even though, when measured against a reference piece, the panel paved (or tiled) might by just that little bit lighter or darker.

Packing and despatch:

Once the pieces have been sorted into shade batches, they are automatically boxed, strapped and, when necessary, shrink-wrapped, before being stacked onto pallets by the robots ready to be sent out to fulfil a particular order or put into a holding area pending delivery at a later date.

The packaging from this plant is primarily cardboard, with plastic strapping. Each box has a bar code which contains all the necessary information, such as product name, size, colour, shade code, date of manufacture, etc. and it's location anywhere within the factory or the stock yard is known at all times.

From northern Italy to almost every major market in the world, porcelain paving is now taking its place in the library of materials we have available to help us design, specify and create stunning pavements and hard-landscapes limited only by your imagination.

This article was produced with the very generous support of Rock Unique, one of Britain's leading importers and distributors of porcelain paving. The factory visit was made possible by Atlas Concorde of Italy