Some definitions

There is a wide and ever-expanding menu of aggregates that can be used as a surface dressing and so, to avoid overcomplicating the subject and repeating the same information over and over again, the term "gravel" will be used throughout these notes. The principles and properties discussed apply equally to cinders, ash, hoggin, or any of the other aggregates discussed, except that the coverage rates given below may be slightly different. Gravel refers to small stones, generally 5-30mm in diameter, that may be angular or rounded. Angular gravels are usually sourced from quarries, a by-product of the crushing processes, whereas rounded gravels are from a fluvial source, such as an old river bed, beaches, and channel dredging. Gravels can be of almost any colour, depending on the parent rock type, or even a multi-coloured blend.

See the Gravel Gallery for more examples of popular British and Irish gravels.

Pea gravel refers to a well-rounded gravel, usually in the 5-10mm size range. It is a popular bedding material for laying drainage pipes.

Self-binding Gravel is a specific blend of aggregates that gives a semi-bound finish. This is considered in more detail on a separate page .

Cinders and Ash refer to the burnt fuel residue from power stations. It is not as freely available as it once was. Pulverised Fly Ash (PFA) is generally too light and the grain size too small to be much use as a surface dressing, but other ash residues and cinders are available in some areas. Colour is usually black, blue-black or deep red.

Red Shale , popular at one time as a surfacing for tennis courts, is a sort-of cinder or ash as it's a partially burnt 'slag' or residue from burning low-quality coal.

It compacts well, forming a hard, dense layer, but can become claggy when wet and so its use has petered out over the last 20 years or so.

It's also heavily implicated in problems with concrete floors in some houses built between 1920 and 1970 or thereabouts. Sulphates within the shale can expand when in contact with moisture so when used as a 'hardcore' fill beneath concrete, this often leads to severe and extensive cracking.

Hoggin is the term given to a mixture of clays, sands and gravels to form a material that compacts well and provides a usable, stable surface at low cost. There is some variation in colour but it is predominantly "buff". We don't have this 'hoggin' stuff in t'north of Britain, nor in Ireland, as we've far more sense and a much better selection of self-binding gravels , but it is popular in the south and east of England.

Crag is a crushed shell product, really only found in the south-east of England and East Anglia. It is said to be less prone to being picked up by foot traffic and is a popular surfacing for horse arenas and in the Royal Parks, apparently. Colour depends on shell type.

Gravels and other surface dressings provide a relatively simple path structure at a low cost. Highly decorative (and costly) aggregates may be used just as well as cheap cinders or limestone chippings. Surface dressing aggregates are ideal for garden paths, and with a good sub-base, they can provide a large drive quickly and at minimal expense.

The gravels most commonly used as a loose surface dressing are in the 6-20mm size range. Anything less than 6mm is more akin to a grit and is too easily disturbed; anything over 18-20mm can be difficult to walk upon. In general, the smaller 6-10mm gravels would be used for footpaths and the 10-18mm gravels for driveways, but it really is a matter of personal taste. One deciding factor could be that, the smaller the gravel, the more the cats like to use it as a toilet!

The size of other surface dressing aggregates is less critical as they tend to "come as they are". Ash and cinders are usually pulverised at source to eliminate any clag that may be over 25mm in size; hoggin is graded to contain only small gravels (usually under 10mm) with the clay binder.

What depth?

If the size of a gravel is the most common question, than the recommended depth is the second most popular question sent in by readers. For some reason, there is a school of thought which believes the gravel needs to be 50-150mm deep to give good cover. Oh, that much gravel or other loose material certainly gives good cover, but it renders the surface virtually unusable!

Have you ever seen those escape lanes at the side of the road on very steep hills or at the side of race tracks? Have you ever noticed what has been used as a surfacing? Gravel. Lots and lots of gravel. Deep gravel. And that's done because, when it comes to carrying a point load such as a wheel, gravel is absolutely useless. The wheel, or the foot, just sinks in and comes lurching to a halt. This happens because there is so little interlock between the individual stones, and so instead of sharing the load between adjacent stones, they roll past each other and 'trap' the load.

The physics is slightly different when a very angular gravel is used, or when a self-binding gravel with lots of fine material is used. Similarly, naturally occurring gravel of mixed sizes and with plenty of fines is often a superb base on which to place foundations, because foundations are NOT point loads, but spread the load over a larger area. Wheels, tyres, shoes, kids' toys - all of these tend to be point loads, where a considerable mass is loaded onto a relatively small area.

Consequently, where a loose gravel surface is intended to be trafficked by people or vehicles, a sub-base is required to act as the load-bearing layer, while the gravel is essential a surface dressing, just there to look pretty.

So: there needs to be sufficient gravel to cover the sub-base or other sub-layers, but not so much that it becomes a 'gravel trap' like those escape lanes.

A thin surface dressing risks being disturbed or scuffed and so exposing the underlying layers, and so we typically recommend the minimum depth be at least twice the size of the gravel being used. Most gravels for decorative use are 12mm or thereabouts, so we suggest a minimum of 25mm. And once you have a depth that is more than about three times the size of the gravel, it becomes too unstable, so with a 12mm gravel, 36mm would be a good maximum, although we usually round up this to 40mm.

Of course, with small gravels, such as a 6mm, a shallower covering could be used, and with larger gravels (say 18mm), a deeper covering, but even so, in the vast majority of projects, 25-40mm depth is just about ideal.

Edge restraints

Keeping It Tidy

Gravels and other loose materials have a lot going for them. They are attractive; they are relatively cheap; they are easy to install. However, if they have one single drawback it is that they rarely stay put. Loose materials are notorious for straying, spreading, scattering and generally getting where not wanted. The technical term for this is 'migration', and although it is virtually impossible to eliminate unless a binder of some description is used, there are techniques that can help keep it to a minimum.

Rule number one is that gravel without some form of edge restraint WILL migrate. This is true even for the cellular systems that are often filled with a gravel. Unless there is some 'check' to prevent it spreading, loose gravel will very quickly extend over a much larger area than originally intended.

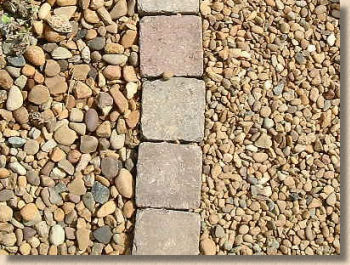

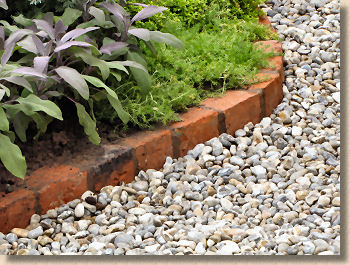

So: an edge restraint is essential. There are plenty of options available, from timber edging boards to concrete kerbs or stone setts .

However, a flush edge restraint, which means one which is level with the top of the gravel, while restricting much of the migration, will not eliminate it. There is too much opportunity for the loose material to be pushed, kicked, trodden or dragged over the top of the bounding edge. Gravel scattered into a lawn is a great way to bugger up a mower!

A better edge restraint is one that provides a degree of check or upstand. This presents a vertical barrier to the spread of the surface dressing, and so there is less migration and therefore less loss of material.

Threshold Restraint

At a driveway or pathway threshold, a vertical barrier is a non-starter for obvious reasons. All too often, the loose material is simply left to abut the adjacent surface, usually a public highway or footpath, where it makes a nuisance of itself by impeding passage of pedestrians, prams and kids' bikes, or gets flicked-up by passing vehicles and chips the paintwork.

A couple of solutions at vehicular thresholds are possible.

Firstly, a Threshold Channel relies on the use of a dished channel to trap migrating gravel and prevent it spreading beyond the boundary by presenting it with the challenge of 'climbing' up the edge of the dished channel. The drawback is that, as the channel fills with accumulated migrating gravel, the 'climb' becomes easier and, unless the channel is regularly cleared, the material soon starts to spread with impunity.

The alternative strategy is to use the reverse of a channel: a hump.

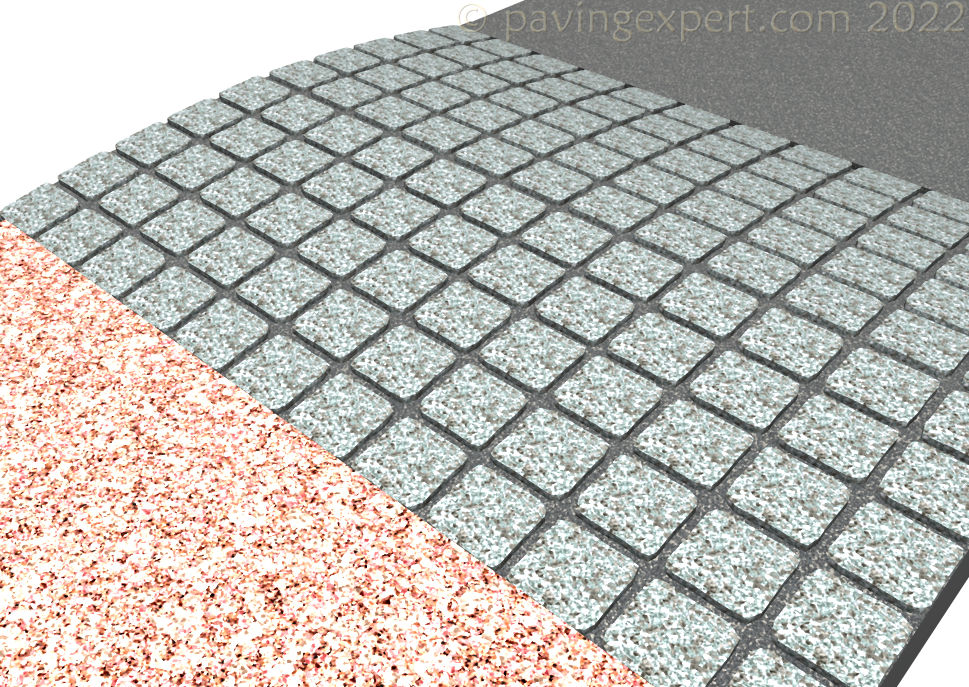

By constructing a humped or 'transverse ridge' of solid pavement (natural stone setts are a favourite material), the uphill climb described for the dished channel discussed above is positioned on the gravel side of the area, and when a sufficiently wide ridge is used (sometimes described as a 'sleeping policeman') little or no gravel at all will manage to escape.

In The Garden

There is also some demand for gravel to be used as a surface for areas of gardens, such as in the currently popular 'Mediterranean-style' gardens. In these circumstances, plants are often placed randomly within the area of gravel, and so it is essential that a reasonable top-soil exists beneath the gravel to provide nourishment and anchorage for the plants.

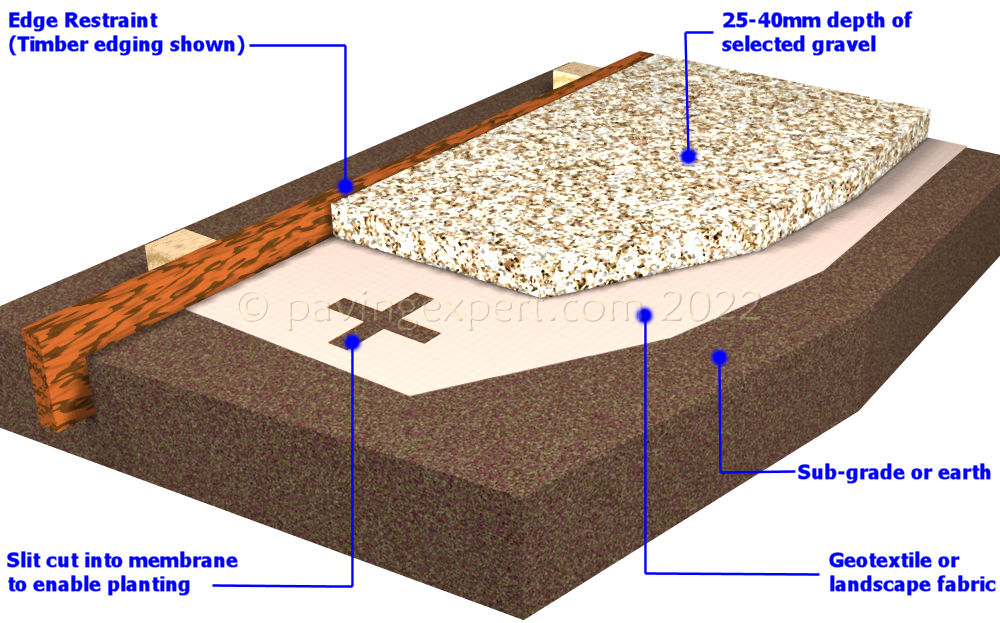

We use a different construction for garden ground cover to that illustrated below for paths and drives. The amount of excavation is reduced to a minimum, and usually consists of little more than skimming off the surface vegetation. Once the chosen area has been dug-off, and any edgings installed, a permeable landscape fabric is laid out over the entire area. In breezy conditions, it may be helpful to weigh down the landscape fabric with bricks or similar, until the gravel has been barrowed in and placed.

The gravel is brought in, spread to a thickness of 30-40mm with a rake, and then compacted with a vibrating plate compactor. Once this is complete, the plants can be positioned as required throughout the gravelled area and re-arranged until the desired effect is achieved. Once the distribution and spacing of the plants is satisfactory, the gravel can be scraped aside from where each plant is to go, the landscape fabric slit cross-wise with a knife, allowing access to the underlying top-soil, and the planting hole prepared.

Once the plant is in its final position and backfilled with soil, the landscape fabric can be trimmed as required and the gravel pushed back around the plant.

Construction

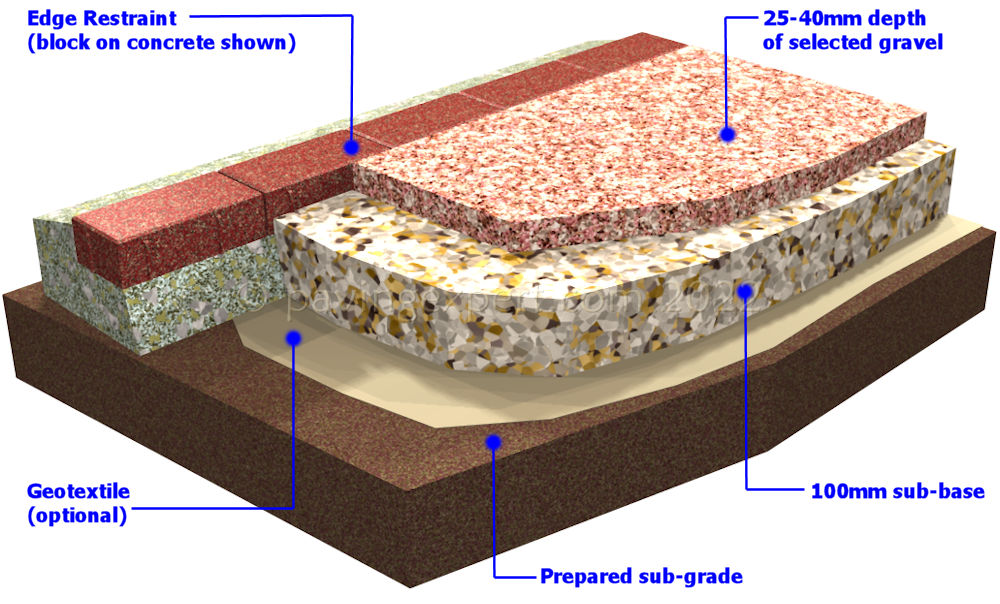

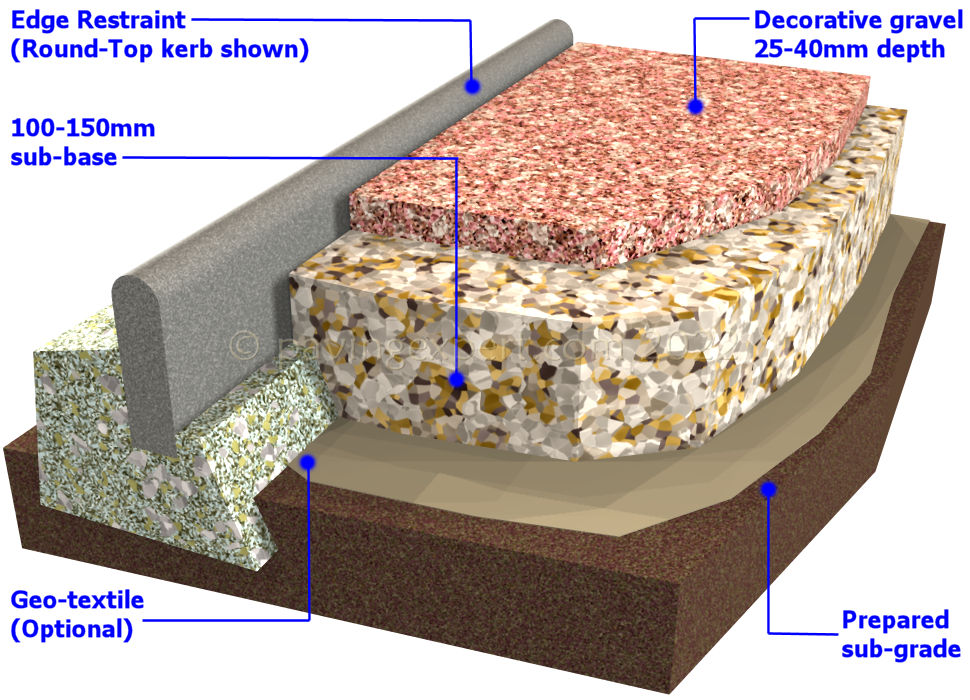

There are 3 layers to a typical gravel pavement, as a bedding layer is not required. The proposed function of the gravel pavement has an important bearing on the construction method used. Separate notes are given for path and for drive construction.

FAQ considering the covering of an existing tarmac or concrete driveway with a gravel

Path Construction

Decide where the path is to run, and mark out as required. See Setting Out page for further guidance on marking out a pavement. It is assumed that the path is to be flush i.e. level, with the existing ground.

Sub-grade

The surface needs to be dug off to a depth of 100mm. Remove all weeds and other unwanted organic matter. If the area of the path is troubled with weeds, the excavated sub-grade may be treated with a general weedkiller such as Glyphosate. Alternatively, a permeable geo-membrane may be used.

Is a geo-textile really necessary and where should it go?

Some thought should be given to whether an edging restraint is required for the path. In gardens, the loose surface dressing can become mixed with surrounding soil very easily. An edging helps to keep the gravel on the path and off the beds. If an edging is required, it should be constructed at this point. Timber gravel boards or a brick edging are eminently suitable.

Sub-base

This layer provides the strength and competence of the gravel path. It should consist of a 75-100mm layer of crushed stone, hardcore or crushed rubble etc., hammered down with a vibrating plate compactor or a punnel. Most Builders' Merchants stock DTp1 , which is an ideal material for a sub-base. Whatever material is chosen for the sub-base, it should contain a good mix of 'lumps' and 'fines' evenly distributed throughout the material. This is to ensure a solid base with few or no voids. A 90mm layer of sub-base material should compact to approximately 75mm although different materials compact differently.

1 tonne of DTp1 granular sub-base covers approx 6-8 m² at 75mm compacted thickness.

Refer to the Sub-bases page for further details on sub-base types and materials.

Surface

Rounded gravels are usually from a marine or river source while angular gravels are a valuable product of quarry blasting. Both are quite suitable for surface dressing a pathway, but angular gravels give a greater degree of interlock, so tend to be more stable underfoot. Ideal gravel sizes for pedestrian traffic is in the range 6-15mm. Smaller gravels tend to disappear into a mush while larger sizes can be uncomfortable or difficult to walk upon.

The gravel can be spread directly onto the prepared sub-base, and then raked out to the desired level as a layer 25-40mm thick. In practice, we spread a thin layer of the gravel over the sub-base and run the plate compactor over it once or twice to embed it into the sub-base. The path is then topped-up and compacted again. We find this helps prevent the sub-base becoming exposed if the gravel dressing is scuffed off.

Coverage rates for gravels are typically 15-20 m² per tonne at 35mm thick. Cinders or ashes may cover 17-23 m².

Drive Construction

Decide where the driveway is to run, and mark out as required. It is assumed that the drive is to be flush i.e. level, with the existing ground. On wet or waterlogged ground, it will be advantageous to install a land drainage system along the edges of the drive. Larger driveways should be cambered (i.e. slightly higher in the centre than at the edges, as most roads are) to assist rapid drainage and minimise waterlogging.

See Setting Out Page

Sub-grade

The surface needs to be dug off to a minimum depth of 135mm, or 180mm for heavier vehicles such as vans and pick-up trucks. Any soft spots should be excavated and filled with compacted sub-base material. Remove all weeds and other unwanted organic matter. On ground troubled with weeds, the excavated sub-grade should be doused with a general weedkiller such as Glyphosate and/or consider using a permeable geo-textile. These geo-textiles can also help to 'stiffen' less firm ground as well as preventing the sub-base being driven into the sub-grade which can result in the sub-grade 'pumping' up into the sub-base.

Is a geo-textile really necessary and where should it go?

If an edging restraint is needed, construct it now, before laying the sub-base. The gravel can become mixed with surrounding soil or lawn very easily. An edging helps to keep the gravel where it should be and off the surrounding grounds. Timber gravel boards , a brick edging or edging kerbs are fine.

Sub-base

This layer provides the strength and competence of the gravel drive. It should consist of a 130mm layer of DTp Type 1 granular sub-base material, hammered down with a vibrating plate compactor or vibrating roller, both available from local hire shops, to an approx compacted thickness of 100mm. For heavier applications, use 180mm of hardcore, compacted to 150mm thick.

1 tonne of DTp 1 covers approx 5 m² at 100mm compacted thickness, and approx. 3.5m² at 150mm compacted thickness.

Surface

This part of the construction is exactly the same as that given above for paths. Any size gravel or other surface dressing can be used for a driveway, although 10mm is the most popular choice. Any aggregate larger than 20mm poses a hazard if flicked up by the tyres of traffic using the driveway.

A harder gravel, such as granite, flint or magnesian limestone is a good choice for driveways. Some of the softer local gravels, such as Cotswold buff limestone or Keuper sandstone, are relatively soft and can be rapidly crushed to dust by repeated trafficking.

It is recommended that the gravel is compacted or rolled to aid settlement, but it may take some time before it becomes thoroughly embedded in the underlying sub-base.

Pros and Cons - Price Guide

- Reasonably cheap and the installed sub-base is suitable to be overlaid at some future date with a different surface, such as block paving or tarmacadam

- Tendency to spread everywhere unless restrained

- May need 'topping-up' at intervals

- Can be treated with a general weedkiller if required

- Very unpopular with burglars because of the crunching noise made when someone walks or drives over it

- Children seem to be very fond of filling gullies with the gravel!