Uses and Applications

Clay bricks used as pavers have been around a lot longer than their concrete cousins . There are brick pavements, still in use, that can be dated back to Henry VIII and earlier. One of the earliest forms of paving, as practised by the Sumerian culture in Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) over 5,000 years ago, relied on using baked clay bricks to form a pavement.

The big problem with clay pavers has always been the cost. To fire up a kiln and keep it burning for the 40-odd hours needed to produce high quality clay pavers is a costly business, especially when compared to the cost of production for modern concrete blocks.

The pros and cons of both clay and concrete pavers are considered on the Choosing Pavers page, but two key features of clay pavers that should be mentioned at this point are that the colours are completely natural and will not fade, and that the pavers themselves are not as dimensionally accurate as concrete pavers, and so they are trickier to lay, which often involves an extra labour cost for Contractors. When choosing clay pavers for any project, these factors need to be balanced – is the light-fast, guaranteed depth of colour worth the additional cost of purchase and installation?

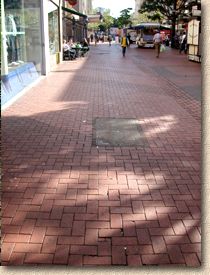

Much of the UK's clay paver manufacturing base is located in and around Birmingham, so it's no surprise that the city has made much use of these local products and laid them in exciting and adventurous ways not seen elsewhere in conservative Britain.

Personally, I love clay pavers, but not everyone agrees with my taste, and the total British and Irish market for clays pavers is barely a twentieth of that for concrete pavers. They tend to be used for 'prestige' civil and commercial applications, where their strong colours and exceptional resistance to abrasion make them an ideal choice for pavements subjected to hordes of pedestrians, but they also have a place in the garden, for patios and pathways with a more organic look, and for driveways where colour and style are paramount.

See this driveway being constructed step-by-step

Laying Choices:

Clay pavers offer a choice of laying technique – flexible paving or rigid paving . These alternative construction methods are covered in more detail on their respective pages and so don't need repeating here. However, the chosen construction method does have an effect on the choice of brick. Some clay pavers are manufactured specifically for flexible construction and some for rigid construction. Just to make things even more complicated, certain pavers can be used for either method, and so it is essential that the manufacturer's technical specification is checked before ordering.

Shapes and Sizes:

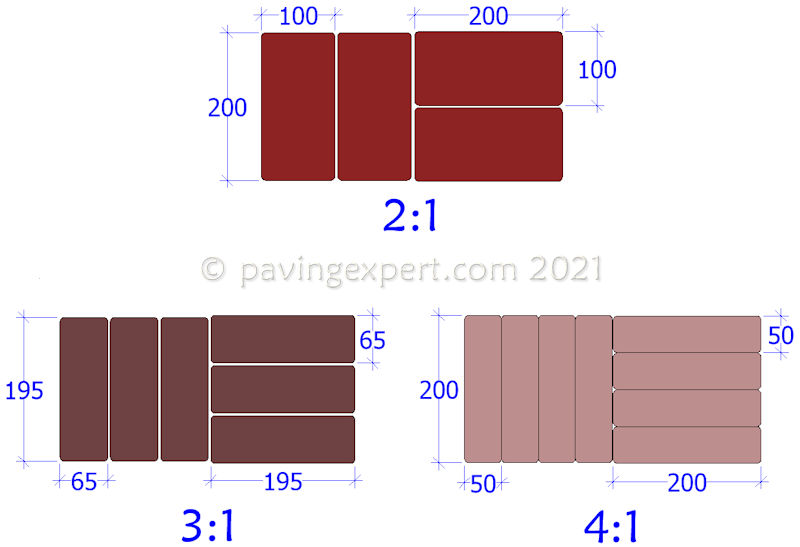

The vast majority of clay pavers are rectangular in plan. The dimensions and proportions of the rectangles are varied, but there are 4 distinct classes of clay pavers:

- Cobbles – usually square and 100x100mm or less in plan

- Bricks – rectangular, most often 2:1, 3:1 or 4:1 in plan

- Oversize – rectangular, but not 2:1 or 3:1, often less than 2:1 - May be known as Pamments, Barn Pavers, or other local terms of affection.

- Specials - non-rectangular, such as Bishop's Hats, Parallelograms, etc.

Dutch Pavers

The sad decline of the British manufacturers of clay pavers over recent years has opened the door for what are usually referred to as ‘Dutch’ or ‘Rhineland’ pavers, most of which come in a plan format of 4:1 or, occasionally, 3:1, and so are quite different to the more familiar traditional British (more specifically: English) bricks that are typically 2:1 in plan format.

Other than plan sizes, there are some noticeable differences between the familiar British clays and their continental cousins, and two of the more important are:

- Dutch clays tend NOT to have spacer nibs, and are therefore laid butt-jointed

- Dutch clays typically have two different faces – a board face and a mould face

The lack of spacer nibs means butt-jointing, which is not something we are particularly comfortable with in Britain and Ireland, but, largely because these pavers are intended to age, to spall and chip and acquire what is euphemistically referred to as ‘character’, the continentals are much more relaxed about it all.

The key, when laying, is not to lay them bang tight, rammed up hard against their neighbours, but to let the wrist remain loose and place the pavers rather than push them, so that there is the slightest of gaps between adjacent bricks. This then facilitates the ability to get some jointing sand between the pavers – not very much, admittedly, but usually enough to ensure the pavement works as intended.

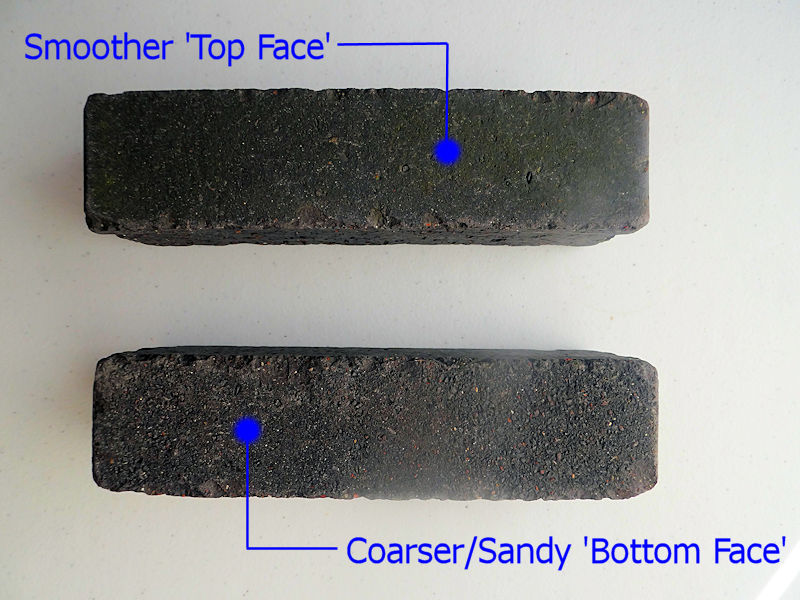

The issue of ‘faces’ arises from the manufacturing process, which is different to the extruded process, more commonly used with familiar British pavers.

Without going into exacting detail, the process results in one face having a slightly rougher (from water mould manufacturing) or sandy texture (from sand-mould manufacturing).

The end result is often a paver with two visually distinct faces, along with two usually identical ‘sides’ and, of course, two identical ‘ends’.

When it comes to laying, if a uniform appearance is required, it requires the laying operatives to sort the pavers to ensure they are all laid either ‘mould face’ up or ‘board face’ up. However, some clients prefer the slightly mottled, random appearance that comes about when pavers are laid ‘as they come’; some mould face up and some board face up.

There’s no structural benefit to laying them one way of the other. It’s all down to personal taste, but, when installing these pavers for a client, it’s always a good idea to explain the difference to them before large-0scale laying commences to ensure they are happy with the effect.

And just to further complicate matters, it’s worth noting that some installations elect to lay the pavers on their sides, so there is no difference in surface appearance!

Regional Types

There are several regional examples of clay pavers, often with a history stretching back many decades before the advent of what we now think of as clay or brick paving. All too often, these regional flavours have disappeared as property owners and highways departments failed to recognise the significance and historical importance of what they had, and so wonderful pavements have been replaced by blacktop or concrete blocks.

One example of a regional clay paver that has managed to survive is the distinctive tile pavers used throughout Southport on the Lancashire Coast of northern England. Before we closed it down , our contracting buiness was involved in the reconstruction of many pavements in and around Southport, re-using the salvaged pavers and helping the town retain its very distinctive styling.

These unique pavers are considered in greater detail on a separate page

Thicknesses:

There are 2 common thicknesses for clay pavers.

- 50mm – for residential driveways and patios

- 60/65mm – the BS pavers as used for footways and carriageways

There are exceptions; some manufacturers offer thicker or thinner pavers.

Colours:

The final colour of clay pavers is determined by the clay used in the manufacture and the firing process. As naturally-occurring clays are so variable, so the range of colours available as pavers is extensive, but they can be lumped together into 4 main groups:

- Reds

- Browns

- Buffs

- Blues

Edges:

Clay pavers have two types of edges – chamfered and square-edged. Chamfered pavers can be used on footways and carriageways, while square-edged pavers are typically used only on footways where a smoother surface is required, such as in shopping areas, where the absence of chamfered joints makes pushing loaded trolleys considerably easier.

Texture:

There are five common textures to clay pavers – smooth, sand-moulded, patterned and drag-face are machine made, plus the hand-made texture.

Although a drag-faced texture may seem to offer better traction than a smooth textured paver, all clay pavers meeting BS EN 1344 offer a minimum level of slip and skid resistance as measured when new and after a significant period of trafficking. These values are known as Unpolished Paver Value (UPV) in new pavers, and Polished Paver Value (PPV) in those units that have been trafficked.

Technical notes: Strength and Tolerances

Flexible pavers are classified as either type PA or PB, depending on intended usage and transverse breaking strength. The classification also dictates the size tolerances, with class PB being much more tightly controlled than type PA

Notes:

Strength:

Minimum Mean Transverse Breaking Load: 10 pavers are tested and the results averaged

Individual Paver Transverse Breaking Load: Minimum strength of any one paver in the test

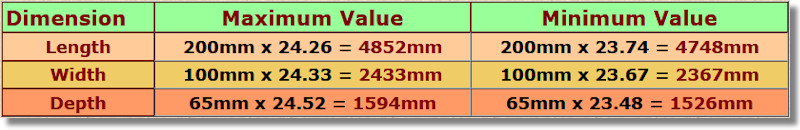

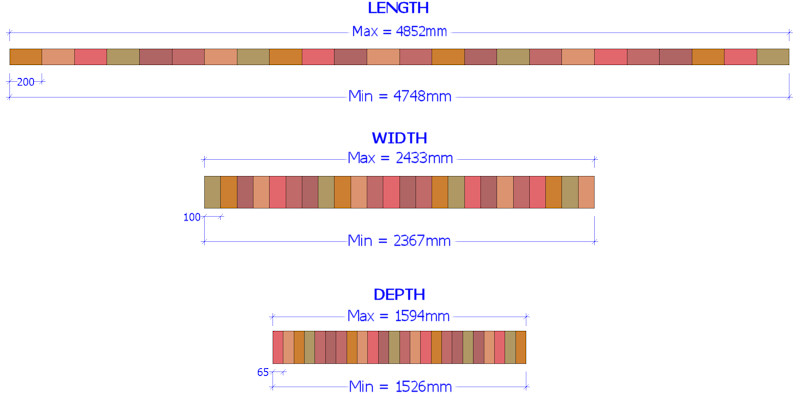

Tolerance: 24 of the pavers are chosen at random from a pack and laid end to end and the total length of the line of pavers is measured. The stated length for that particular paver is multiplied by the values given in the table above, and the result is checked against the maximum and minimum values calculated. The procedure is repeated for width and for depth, in much the same fashion.

For example, a type PB paver stated to be 200x100x65mm should, when laid in lines of 24, be found to be within these limits….

Construction:

For flexible construction, clay pavers are laid in exactly the same way as concrete blocks – a screeded bed of grit sand is prepared, the blocks are laid by hand, cut-in and compacted. However there are a couple of points that should be mentioned in regard to the laying of clay pavers.

Firstly, they are very hard, they are not perfectly flat, and therefore they tend to be much more difficult to cut in a standard block splitter. There are specially-developed splitters for use with clay pavers, but most contractors now choose to cut them using a power saw with a diamond blade, or a bench-mounted masonry saw.

Secondly, they can be spalled during consolidation by the action of the plate compactor. For this reason, many manufacturers suggest that a surfeit of jointing sand be left on the surface during consolidation, so that it can act as a cushion between the plate and the pavers.

However, we find that using a neoprene sole attachment (or a spare piece of polyethylene foam - medium density non cross-linked expanded polyethylene foam sheet - as shown in the photie opposite), fitted to the base of the plate compactors, gives much better results, as it protects the pavers but doesn't grind the jointing sand into the surface, which is known to cause unsightly (and damned hard to shift!) stains.

On the subject of jointing, clay pavers usually require slightly more jointing sand per square metre than concrete pavers of a comparable size. This is because of the imperfect nature of the pavers, which results in the joints being slightly wider than would be found with concrete blocks. The difference is usually around 15-25%, so, where a standard 40kg bag of jointing sand might be sufficient to fill all the joints of a 16m² pavement constructed using 200x100x60mm concrete blocks, a similar area of 200x100x60mm clay pavers might require 50kg.

Also, as the imperfect nature of clay pavers results in some joints being 5-8mm in width, there can be a problem with 'scour' during the first few months after construction. This is the phenomenon whereby surface water or vigorous sweeping can remove jointing sand from open joints.

If this becomes a problem, then the joints should be re-filled and treated with a joint stabilising fluid to keep the sand in place until such time as natural sealing by means of detritus takes place.