Introduction:

This is a popular enquiry from the DIY readership of the Pavingexpert website. Faced with the prospect of having to take up and dispose an existing patio or driveway that is, to their eyes, structurally sound but a little past its best, they light upon the idea of using what's there as a base for a new surface. Something in the deepest recesses of their mind tells them that it's probably not kosher. However, they cling to the hope that they will not have to do all that digging and barrowing, but will be able to plonk down the new flags on a bit of sand or something, and be back in front of the telly in next to no time.

No professional contractor would lay new paving over the top of existing paving, unless there were extenuating circumstances. One notable exception would be the use of a bitmac overlay, where a new surface or wearing course is applied over an existing bitmac (or occasionally concrete) surface to improve the overall look and styling, but, when it comes to segmental paving, it is considered to be 'bad practice' to lay new paving over old.

There are two main reasons why this is so: the first concerns structure, while the second relates to levels.

Structure

The structural argument against overlaying of segmental paving is based on the reasoning that the 'buried' paving units may move or settle and because they are of a relatively large size, such movement/settlement is likely to cause a problem in the support of the overlying paving. This may be quite apparent in a case where, for example, large 900x600mm flags are to be overlaid with 450x450mm flags or block paving, but is less obvious when the 'buried' paving units are smaller, such as block paving or small patio flags.

Consider an existing pavement of 600x600mm flags that is to be overlaid with decorative patio flags of 300x300mm, 300x450mm and 450x450mm. Unless the existing flags are lifted and the construction examined, there is no way of knowing whether the structure is capable of supporting the additional weight/loading of a permanent over-layer of bedding and paving. If the existing paving is poorly laid, or has been laid on unacceptable spot-bedding , the permanent imposition of an additional 60-200kg per square metre (depends on paving/bedding type and thickness) may be sufficient to cause movement, settlement or collapse of the whole pavement. Even if the pre-existing bedding seems sound, it may not be adequate to support and distribute all that extra weight.

Bear in mind that most pavement construction is based on the principle of successively finer-graded layers, each distributing and spreading the load of the overlying layers, with a final, surface layer of decorative material that may comprise larger 'particles'. Having a sub-layer of 'large particles', such as flags or blocks, contradicts this principle.

It is always best practice to be aware of just what lurks beneath. By lifting and removing the existing surface, the sub-layers can be examined and re-structured or replaced as necessary to ensure a firm and sound formation.

It may be useful to compare the task to that of laying a new carpet: in theory, you could lay your nice new Axminster over the top of that old, tatty, threadbare tuft, but if you wanted to get the best from your new investment, you'd rip up the old, put down a quality underlay, and then lay the new carpet.

Re-using old bedding

When replacing existing paving, even when the new paving comprises units that are shallower than the previous, it's rarely a good idea to leave the old bedding in place. That bedding was created for a different paving, the old ones, and it may not be entirely suitable.

With rigid/bound bedding (mortar or concrete) it is highly unlikely that the old bed will perfectly accommodate the new paving, so it should be removed prior to laying new.

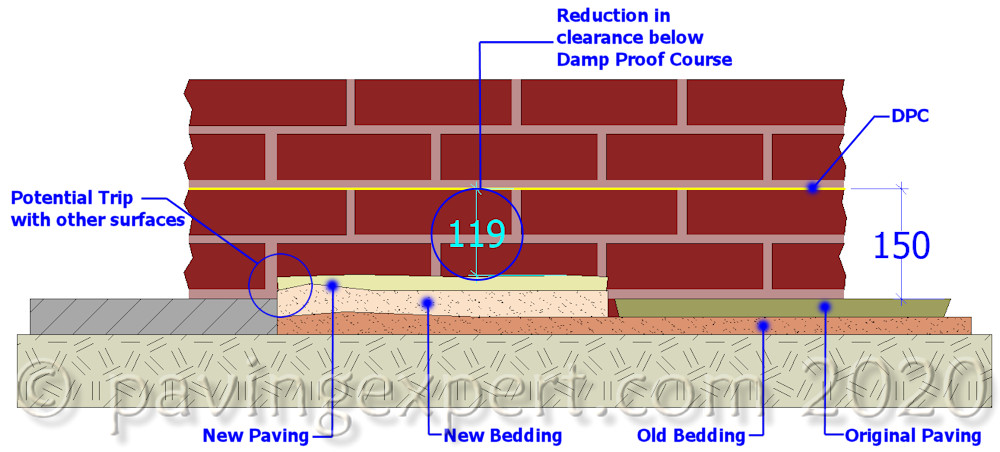

There may be a temptation to lay a new bed directly over the old, but this, too, is not always a sound plan. The old bedding may well be degraded or fractured or weakened in some way, so is best to replace it. And there's also the consideration that adding a new bed could elevate the new paving to a level that causes other problems, such as conflicts with existing levels or reducing the distance between paving and DPC to less than 150mm.

With loose, flexible, or unbound bedding (sand or grit) it is known that the effectiveness of such bedding deteriorates over time. It becomes contaminated with 'undesirables' such as weeds/roots, silts and muds; it degrades due to individual grains becoming crushed to a smaller size and increasing the quantity of 'fines'; it loses particle angularity which adversely affects interlock. Overall, the best practice is to *always* replace loose, flexible, or unbound bedding.

Levels

The second argument against over-laying is that of levels. All paving and surfacing should be at a level that is at least 150mm below that of any DPC or internal floor level (except at doorways and in exceptional circumstances). Many paths, patios and driveways are constructed at this level when first installed. Consequently, any overlay would reduce the separation between DPC and paving.

Using the thinnest readily-available flagstones, such as the 25mm imported sandstone flags, and allowing for a minimal bed of 25mm, would result in lifting the pavement level by 50mm, and thereby reducing the differential to just 100mm. As should be obvious, using thicker pavings, such as a 40mm wet-cast flagstone or a 50mm block paver, would result in an even more drastic reduction in the differential.

As mentioned on the All about DPCs page, breaching the 150mm rule won't result in a prison sentence, but it can and does adversely affect property valuations, and there is a strong possibility that any insurance claim for damp arising from installation of a pavement to incorrect levels would be rejected. However, on private property, it is a decision for the property owner: if they elect to ignore the 150mm rule, then they will have to live with the consequences. Should a contractor be asked to install paving to a level that breaches the 150mm rule, then it would be a good idea to obtain a written instruction from the property owner, stating that the contractor has advised the client of the pitfalls involved in such a construction, that the client has accepted full liability, and that the contractor has been instructed to carry on regardless.

Construction Methods

Preparation:

So: if the property owner does decide to ignore all of the previous advice, what sort of construction should be used? The first thing to consider is the condition of the existing paving. If it is loose, sunken, rutted, weed-ridden, or sub-standard in any way, some remedial work may need to be undertaken before laying the new. Any loose or rocking segmental paving (flags, blocks, setts, etc.) should be removed and either re-laid to be firm and sound, or replaced with cement-bound material (10:1 grit sand with cement or a ST1 lean mix concrete ).

If the substrate is a monolithic surface, such as concrete or bitmac, any significant cracks or movement joints are potential problems, as they could well be the source of reflective cracking in any new monolithic surface, when laid.

It's also possible for pre-existing cracks and movement joints to cause problems in segmental pavements. Any propagated crack is most likely to emerge in a joint within the new paving, rather than damage any of the new paving units. However, any such propagated crack is still liable to cause movement or settlement of the new paving.

Any movement joints should be deliberately carried through into the new paving. With a bit of judicious jiggling, it is usually possible to align a joint in the new surface with the 'buried' movement joint, although it may be necessary to create a joint specifically to extend the movement joint.

Consider the proposed use of the new paving. On older properties with concrete or granolithic paths, any cracking or settlement is likely to have stabilised - if there's established vegetation in the cracks and no sign of any recent movement, it may be acceptable to use the path as a substrate for a new, light-use, foot-traffic only pavement. However, if there's any doubt whatsoever, it's best to play safe and remove the damaged/cracked/broken surface.

Bedding:

Any weeds should be removed, along with any organic detritus. Sweep the surface clean to remove any loose material, litter, soil, etc., and douse with a good weedkiller, if necessary. Bearing in mind the consideration regarding additional weight and DPC levels, it would make sense to minimise the depth of the bedding layer.

Flags can be laid on 20-25mm of cement-bound material – the 10:1 bedding mix described on the Mortars and Concretes page is ideal for this task. A semi-dry or moist mix is easiest to work, although a wet mix can be used if preferred.

Block paving is best laid on 30-35mm of grit sand, as described in the Block Paving section . Any less and it can be very difficult to consolidate the blocks. However, rigid block paving can be bedded onto 15-20mm of Class II mortar.

Setts, cubes and cobbles are best laid as described on the relevant pages. Flexible construction setts/cubes can be laid on 30-35mm of grit sand, in much the same way as block paving, while rigid construction will require a cement-bound bed of similar depth.

CarpetStones ™ and similar products should be laid on a 20-25mm thick bed of the 10:1 bedding mix.

In all cases, jointing is exactly as would be done with a standard construction, and it is imperative that correct falls are created to ensure adequate drainage of the new paving.

Other FAQs

- Flags:

- - Circular Stains on new flags

- - Laying paving over existing paving/surfacing

- Block Paving:

- - Working out screed depth

- Bitmac:

- - Soft and Sticky Tarmac

- - Fuel leaked onto tarmac surface

- Gravel:

- - Gravel over existing surface

- General Construction:

- - Efflorescence

- - Is a sub-base necessary?

- - Is a membrane necessary?