After years (and years!) of wrangling and wrestling and re-writing, the first part of the revamped British Standard 7533 was released into the wild back in late summer, but, as is always the way with these things, it will take a while to become more fully embedded, and to that end, an explanatory webinar was staged on Wednesday, October 20th, to help spread the word.

You should be able to view the Webinar via this link

As you will obviously know, BS7533 is the “bible” for our trade. It’s a series of standards that cover the design, installation and repair of modular paving, which includes flags/slabs, block pavers, clay pavers, setts, cobbles, kerbs, channels and permeable paving. Over the decades since its original inception, it has grown and by the start of this decade encompassed no less than twelve sub-documents, each dealing with one aspect of modular pavement construction. It had become something of a challenge to remember just where the relevant bit of info could be found. Was the design depth for a block paver sub-base in 7533:3 or was it in part 1? And isn’t there a bit in Part 7? Or was that something else?

It had all got a bit confusing, even for those using the documents on a regular basis. So, the decision was taken to simplify it all, to more-or-less start from scratch and re-organise it to, hopefully, make it simpler to follow and easier to find the relevant information.

All of the design information would be bundled up as a new Part 101, while all of the installation information would go into a catchily titled Part 102, and because it’s still a little bit “out there”, information for permeable modular paving would go into….can you guess? Part 103!

Part 101 was wrapped up this year, pulling together all the information needed when *designing* any modular pavement, and work has started in earnest on Part 102, which is focussed on the installation techniques, working practices and methodologies. Part 101 determines *what* to build, while 102 is aiming for *how* to build. They are complementary, working best in tandem, but, in the most general of terms, Part 101 will be predominantly used by those designing modular pavements, while 102 will become the new handbook for those that actually build those modular pavements.

So: has anything changed? Will we need to change how we work, or re-think how we design and specify paving works?

Obviously, the publication of a re-vamped British Standard presents the opportunity to update, to embed the latest thinking, incorporate the contemporary technology and research findings so that we will design (and eventually build) modular pavements that are fit for the 21st century, and more relevant to the way we live and work today, with a far wider range of materials, vastly improved understanding of the possibilities with mortars and concretes, and, of course, the use of ever bigger trucks, wagons, and lorries.

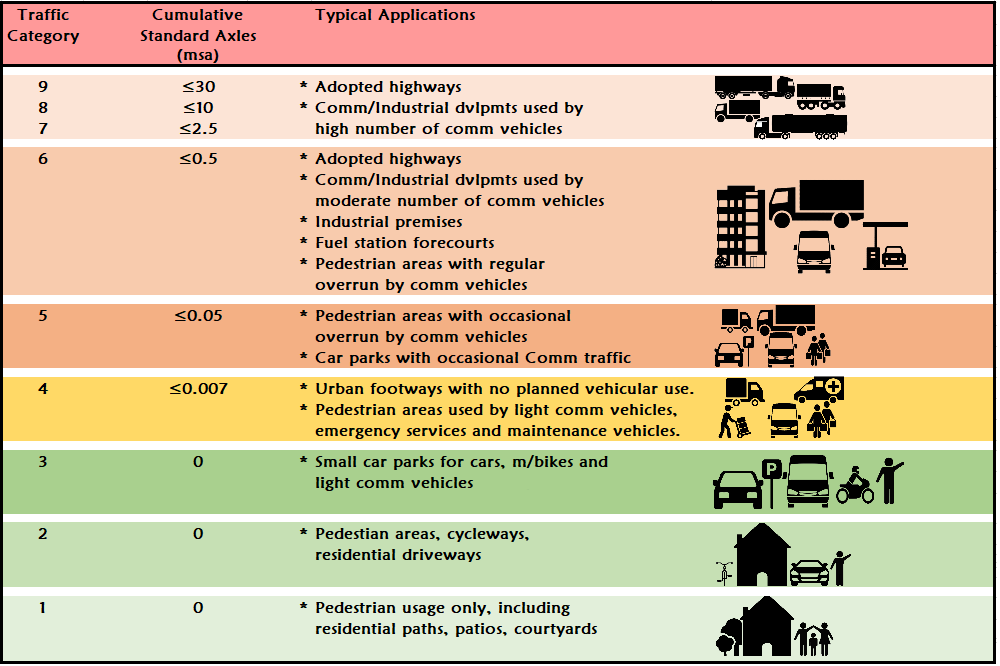

Probably the biggest change, and one that is absolutely central to the design process is the expanded definitions of Traffic Categories. This is neatly summarised in Table 2a (for unbound construction) and Table 2b (bound construction).

Previously, we had sort-of four-ish traffic categories from Class 1 (big, heavily trafficked, big loads pavements) to Class 4 (patios and driveways), but some of these classes were sub-divided to reflect different uses, and it all got a bit confusing. Now, we have nine clearly defined and easily understood Traffic Categories, starting with the new Class 1, which is residential paving with no vehicular use (so: a patio or pathway), passing through Class 3 (your average residential driveway or small ‘pub car park), right up to Classes 7, 8 and 9 which are adoptable highways with varying levels of traffic.

There are all sorts of conversion factors and modifiers that can be applied to ensure the most appropriate Traffic Category is selected prior to the actual design work starting, but it is all reasonably straightforward, and, more importantly, it’s all in this one document.

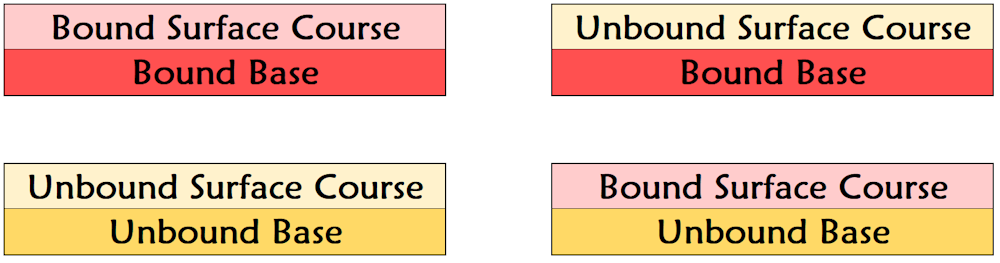

The other notable item from all of the above is the very definite move away from the previous, somewhat vague terms of “rigid” and “flexible” construction, to the far more definitive “bound” and “unbound” construction. It’s almost self-explanatory: unbound means the constituent parts are loose and free to move, whereas bound means they most assuredly are not.

The design process divides the construction work into two “groups”: those with a bound base (usually a layer of macadam, AC, concrete, etc.) and those with unbound bases (sub-bases, most commonly.) This brings about the possibility of four pavement types:

By requiring the whole of the pavement structure, from sub-grade right up to paving layer, to be considered during the design, the new 101 document will, hopefully, promote a more coherent design process by compelling the engineers (normally responsible for designing the sub-bases and bases) to cooperate more fully with designers/landscape architects, who normally get the job of choosing paving materials. On the lower traffic category projects (Classes 1-4 – patios, driveways, small car parks, etc.) the entire design often falls to one person, usually the installer/contractor, and Part 101 introduces no additional tasks, but for the higher traffic categories, it will require what we might call “enhanced cooperation” between the parties involved and so produce better, longer-lasting, lower-maintenance pavements.

Another significant advancement is the requirement to consider how moisture on and within the pavement is handled. For too long surface water and moisture within the build-up layers has been a secondary consideration – just send it somewhere else and let the next poor sod worry about it – but Part 101 makes it a key element of the design thinking, and heavily promotes the use of quality materials and modern advances in mortar technology. By prompting better management of moisture in particular, we will, it’s hoped, see fewer problems and pavement failures in the years ahead.

It has been no easy task taking twelve often disparate and slightly confusing Standards and distilling the design elements into one, coherent new Standard, but it needed doing, and, while it may not be perfect (anything produced by a committee is always a compromise), it is an improvement and, when implemented, most definitely will result in superior pavements. There will be some relatively minor changes required in some working practices amongst the design and engineering communities - and quite a bit of work for me in updating this gargantuan, sprawling website – but, as I wrote somewhere else this week, any trade or industry that doesn’t navel-gaze occasionally and seek improvement, is destined to decline and to ultimately fail.

BS 7533-101 is the first major improvement in the paving trade for at least a couple of decades. It will take time to implement, but we should start seeing its effect pretty soon. Meanwhile, Part 102, the new Standard dealing with HOW paving is laid, is now in preparation and that should make significant advances on the installation side of the industry. 102 is pencilled-in for early 2022 but, as we’re all aware, the best laid plans of mice and men…..

You can download your own copy of BS 7533-101 via this link

Any commission earned is used to fund the hosting and maintenance of this website