This page extends the coverage given on the previous pages which considered the techniques involved in Concrete Paving Manufacaturing and Paving Textures and should be read in conjunction to those pages.

Introduction:

The purpose of secondary processing is to add value to a standard paving unit by creating a special texture. Some secondary processes, such as flame-texturing of stone, can be applied immediately following primary production, but, in the case of concrete and clay products, most of the secondary processing techniques have to be delayed until the paving units have cured or hardened sufficiently to withstand the stresses and rigours of the texturing processes. Where a product has to be stockpiled while it readies itself for further texturing, this imposes additional costs on the manufacturer, which explains why some textured products are so expensive compared to the standard units: not only is there the extra cost of secondary processing, but the units have to be stored for a period prior to the processing.

The most popular secondary processing techniques are:

These are, generally speaking, destructive processes, and so only high-strength units are suitable for secondary processing. Accordingly, items that will be processed are almost always press manufactured , rather than wet-cast , as that manufacturing method produces tougher, harder, more resilient units capable of withstanding the duress of secondary processing.

Tumbling

This process, which is also known in some quarters as "Rumbling", involves deliberately damaging the cured units to give them a weathered or aged appearance. The most common method is to dump the units in the equivalent of an empty concrete mixer and churn them around and around so that they bash against each other and against the sides of the revolving drum, knocking off the arrises and corners in the process.

This process has two notable drawbacks: as the drum rotates and the pavers pass through, there is no accurate control over the amount of damage inflicted to the pavers, and so the output has to be checked by operatives to remove those units that are so badly damaged that they cannot be sold. Obviously, the average amount of time each paver spends within the drum can be adjusted by speeding up, slowing down or tweaking the alignment of the paddles inside the drum, but this is a relatively coarse adjustment.

The second drawback is that the tumbled units are dirty. They become covered with a fine dust that is hard to remove, and so, when the product arrives on site, it can be hard to justify the premium price paid for a product that looks gnarled, battered and filthy. Luckily, the weather in these soggy islands is such that, after a couple of weeks out in the open, most of the dust and detritus will have been washed away and the inherent beauty of the pavers can shine through.

To overcome these problems, one manufacturer ( Ebema Stone & Style ) has developed (and very wisely patented!) a unique 'distressing' process that allows the degree of damage to corners and arrises to be finely controlled, while simultaneously removing almost all the dust generated by the process, and, importantly for manufacturers, the units are maintained in a single layer, thereby enabling fully automated handling with no human intervention.

And of course, tumbling can be applied to stone: in fact, stone pavers were the first products to be subjected to the process, long before concrete and clay pavers became popular.

Although it's impractical to tumble larger elements such as flags, cubes and setts are eminently suitable candidates, and the latest development sees relatively small, tumbled setts glued onto a mesh backing, allowing pre-determined patterns to to created and laid with ease.

Shot Blasting:

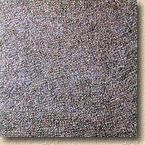

This technique is used to impart a lightly roughened texture to one or more surfaces on the paving units. With blocks and flags, it's normally only the top surface that is treated, as the sides and base are not visible when laid, but with kerbs, the top and roadside face would be treated, and some units may actually be treated on 3 sides or more.

The basic process involves peppering the units with shot, which is small beads of steel, fired at high velocity by means of compressed air. The shot spalls the surface a bit at a time, dislodging small particles of concrete, and the debris falls to the floor along with the shot. The debris and shot are removed and separated, with the debris sent for disposal while the shot is recycled to be used again and again in texturing further units.

Unlike tumbling, shot-blasting produces an even degree of texturing that can be finely controlled by adjusting the time spent in the blast chamber, and the textured product is relatively clean, as the shot dislodges any dust as it batters the paver surface.

However, one problem with shot-textured products, particularly the lighter-colours such as 'Natural' (Grey, in non-marketing speak) and Buff, is that they become noticeably dirty very quickly. The rugged surface provides an ideal home for the usual grime and for colonising vegetation such as algae and lichens.

Thankfully, their characteristic good looks are easily restored by a good scrub down with a power washer, as evidenced in the photo opposite, where the unwashed flags on the right contrast sharply with the 'rejuvenated' flags on the left.

Bush Hammering:

In this process, the surface of the units is pummelled by a series of pyrimidal chisels mounted as a hammer. The hammer repeatedly strikes the unit, picking away at the surface to create a roughened, natural looking surface, similar to that produced by shot-blasting.

When applied to stone paving, such as granite, the resulting texture is sometimes classed as 'Fair Picked' for the purposes of BS435 which specifies the acceptable dressing of stone for highway use.

The main differences between Bush-hammering and shot-blasting are that bush-hammering is usually applied to only one surface, whereas shot can be blasted at 2 or more surfaces simultaneously, and the texturing produced by the bush hammer can be repetitive (see the image of bush-hammered granite below), unlike the shot-blasted texture which is truly random. The ability to aim the bush hammer at a specific point can be used to create patterned textures, with parts of the paver treated while other parts are left in their original condition. This effect is best seen on those pavers where an untreated border is left surrounding a textured panel.

The hammered surface emerges from the process relatively clean, as any loose debris tends to be blown off the treated surface by the hammering process, and, in some instances, a jet of compressed air aids removal of any dust.

Polishing:

This technique is alternatively known as "Grinding" - the prevailing usage seems to be that natural stone pavers are 'polished' (or 'honed', just to confuse matters even further!) while concrete units are 'ground'.

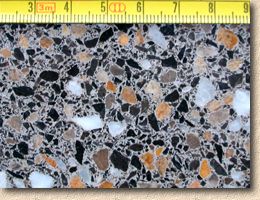

The top surface of a unit is ground down (or honed or polished - you choose!) using an abrasive paste which often contains a carborundum powder. With concrete pavers, this has the effect of removing the fine matrix often found on the surfaces of press-manufactured units and exposing the coarse aggregate within the concrete. This has obvious benefits where a decorative or coloured aggregate has been used, as the ground unit is given a terrazzo-like appearance.

Unlike the shot and hammer textured finishes discussed above, concrete paving units with polished or ground surfaces tend to remain relatively clean, as the incredibly flat surface offer less purchase to grime and vegetation. And despite what some people seem to think, the ground/polished surface does NOT make them slippery - in fact, all BS paving has to meet minimum requirements with regard to "Slippiness" (technically known as the Polished Paver Value or PPV).

This makes them a good choice for garden patios and the like, as they need less cleaning than the heavily textured offerings, and are very easy to maintain.

For stone paving, especially the igneous and metamorphic types such as Granite, Porphyry, Marble, etc., polishing has the effect of, literally, "buffing-up" the stone, enhancing its natural beauty.

The polishing or grinding process removes only a millimetre or so of the surface and the treated surface has to be washed clean following processing to remove the abrasive past and the ground concrete residue.

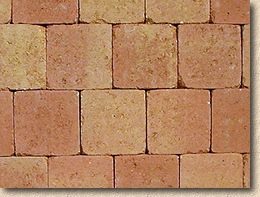

Wash-to-expose:

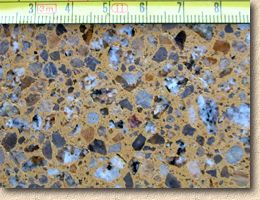

This is a highly specialised treatment that is not often seen on pavers used in Britain and Ireland but is quite popular in continental Europe. It differs from the previously described processes in that the treatment takes place immediately after manufacture, with no 'waiting period' while the paver cures. The finished effect is a uniquely textured product where the exposed coarse aggregate is displayed to best effect, making the most of its natural colour.

The process is usually applied to 'face mix' products. This is a method of manufacturing favoured in many parts of the world that uses a 'no frills' base concrete topped with an 8-10mm layer of high-specification concrete.

The aggregates and matrix for a washed paver are specially selected for best performance, and, as soon as the paver emerges from the press, the units are elevated at an angle and washed with a jet of water which removes much of the surface matrix along with a small quantity of aggregate, but leaves behind an exposed layer of the decorative aggregate.

The great advantage of this type of texturing is that the colour of the paver can be wholly delivered by the inherent colour of the exposed aggregate, with no need to use expensive cement dyes, even the best of which are subject to fading in UV light. Different colours of aggregate can be blended to create original hues and the random alignment of individual grains of aggregate within the surface imparts a glinting, crystal-like quality to the finished product.

The largest supplier of these washed/exposed pavers in Britain is Stone & Style , a Belgian-based company with almost 50 years experience of paver manufacture and acknowledged to be the leading European producers of this type of paving, which they market under the name class="pxp"Rockstone™

The paver shown opposite is a Buff 200x200mm block.