Introduction:

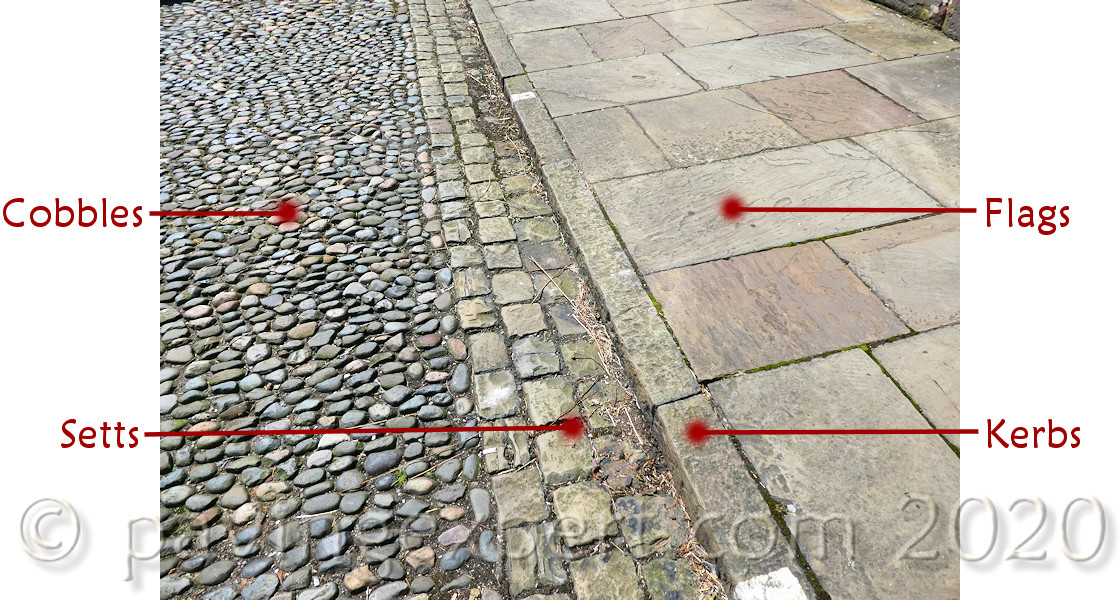

Cubes and setts, cobbles and cobblestones. The terms seem to be interchangeable, depending on your location. There's a whole range of regional terms, too, such as "Cassies" or "Nidgers" in Scotland, and "Belgian Block" in some strange places in southern England. The terms refer to blocks of natural stone, hewn from a quarry, in a range of sizes and rock types, and "cobbles" or cobblestones is also the name given to large, rounded beach pebbles 200-400mm in size, which are sometimes called 'Duckstones'. These rounded ' cobbles ' are discussed on a separate page. The general public tend to refer to the gritstone 'Hovis Loaf' type as Cobbles, although the correct term is 'Setts' - these range from 100x100mm to 200x250mm in size, and have an average depth of 150-200mm.

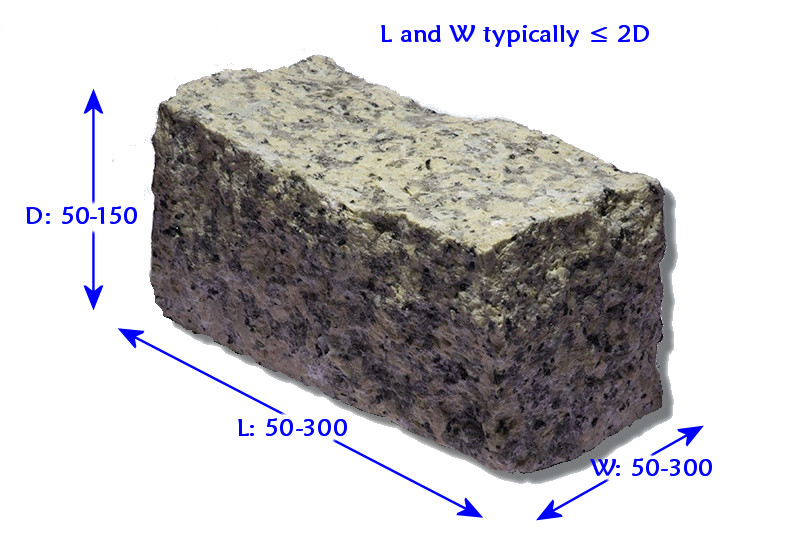

To be technically precise (ie: according to BS EN 1342:2001), a sett is a dressed block of stone having plan dimensions that are 50-300mm in length, and a thickness of at least 50mm. The length and/or width should not usually be greater than twice the thickness. However, some decorative setts for garden use may be only 25mm or so thick and 100x100mm or even larger, in plan.

A cube is a type of sett, one which has all three dimensions roughly equal.

Cubes tend to be used for more decorative work, particularly fans and bogens, which are considered later on this page. While there are setts and cubed with perfectly accurate sawn faces, most new cubes are split or cropped and there is an urban myth that, somewhere, there exists a cropped ube that has all six sides exactly orthogonal, the 'perfect cube'. In over 50 years working with cubes, I've never seen one yet!

Whether they are cobbles, cubes, cassies or setts, they are excellent paving products and will last for many, many years; in fact, some of the stones currently covering the streets of Britain and Ireland have seen over 200 years of continual use.

Their pedigree as a paving unit goes back to the Romans, 2000 years ago, and beyond, and they are characteristic of most of the so-called 'historic' towns and cities of these islands. They are fast becoming an essential ingredient in the nostalgia business, as the fashionable designers and developers fondly remember their long-lost days of childhood, sitting on a kerb-stone, twirling sun-softened pitch onto lolly sticks in the streets of post-war Britain.

Uses and applications

Nowadays, new setts are produced to regular dimensions in a wide variety of finishes, and are often laid in the same manner as modern concrete block paving . The reclaimed stones can be difficult to lay, mostly because of their inherent randomness, but whether new or reclaimed, when they have been laid correctly, they are a beautiful sight, and make superb paths, patios and driveways, as well as visually stunning areas of civic paving.

As with many other small element paving units, they offer superb possibilities for design. Their natural colouring, which will not fade as do some concrete dyes, and the range of textured finishes bring an extra dimension to paving design, whether it be the re-creation of traditional cobbled streets or an unique and original design for a public area.

Setts are popular for the creation of impressive large-scale patterns in civic paving schemes, such as the popular European Fan Pattern and these magnificent guilloche swirls outside St. Georges' Hall on Lime Street, in Liverpool.

A centre-stone cut from a yorkstone flag is surrounded by 10 courses of granite cubes, then 2 soldier courses of grey-black basalt setts edge a figure-of-eight pattern laid in blue-black long setts. The pattern is bounded by a double channel course of the dark blue-black long setts, and infill paving is done in the lighter-coloured granite cubes. Overall, the pattern is approximately 6 metres in width. What other paving material could give such a stunning look?

Types

There are three main types of rock in the world and they are all used for the production of setts; sedimentary, metamorphic and igneous. Sedimentary rocks, such as sandstone or siltstone, are relatively easier to cut and shape. Metamorphic rock, such as Gneiss, Quartzite or Marble, may retain some of the cleavage planes of its sedimentary ancestor, which is not always a desirable trait, and so this type is rarely used. Igneous setts, such as basalts and granites, are usually much harder and have few, if any, cleavage planes.

Sedimentary setts are still quarried from the Pennine gritstones of Northern England, although more and more hand-hewn setts are being imported from foreign climes, particularly southern Asia, where labour costs are much lower. Many of the UK-produced sedimentary setts are sawn from quarried rock, and may be further processed. This has enabled the development of modular sett paving, which is discussed below.

Igneous rock types are particularly popular for cubes, although setts are often hewn from granites, basalts, diorites and gabbros. Many of the reclaimed igneous setts and cubes are of British or Irish origin, notably the granites of North Wales, Cumbria, Cornwall, Wicklow and Scotland, but more and more of the new materials are imported from other countries.

Igneous rock tends to be denser than sedimentary rock, and its crystalline nature of makes it much harder to cut with hand tools than most of the sedimentary types. It will rapidly abrade standard blades on power saws, and so, if it must be cut with a saw, a diamond blade is strongly recommended. However, on reclaimed materials the dead straight lines created by power sawing looks awry with the natural finish of these units, so we often ' fettle ' a sawn edge (ie, nobble with a hammer) to give it a more natural, hewn appearance.

Sizes and Tolerances:

It can seem that there are almost no limits on the sizes of setts and cubes, but as mentioned previously the relevant standard BS EN 1342:2001 gives some guidance, in that setts should not be more than 300mm (ish) in length or width, and neither of the plan dimensions (length and width) should be more than twice the thickness, which suggests a maximum thickness of 150mm.

Obviously, there are exceptions. Some reclaimed materials would not meet these precise sizing requirements, and, occasionally, local tradition will result in the use of setts that are larger than the maximum stated dimensions - some setts being laid in Scotland are 200mm thick, for example.

Setts are hewn natural stone and so there is almost inevitably some 'inaccuracy' in the planned dimensions. These inaccuracies are regulated by having a permitted tolerance, a specified maximum variation in size, and because the different finishes available affect the dimensional accuracy, the 'rougher' finished such as cropped/hewn are given more leeway than that for, say, a sawn or textured finish. Although there are 'complications' which are sketchily outlined in the standard, generally speaking cropped/hewn setts and cubes are allowed a tolerance of ±15mm, while sawn/textured setts and cubes are only allowed ± 5mm.

This tolerance leads to a somewhat informal method of material specification for cubes. Given the rather generous tolerances, cubes are often described by a pair of values which indicate the minimum and maximum sizes, in centimetres.

So, the most popular sized cube, which has ideal sizes of 10x10x10 cm, is assumed to have a plusmn;1cm tolerance and is therefore described as a 9-11 cube, that is, cubes with sides that will be between 9cm and 11cm.

When ordering new cubes, it's usual to specify this dual-number reference, which is explained in the table opposite.

It's worth noting that, with cubes, when the laying pattern is to be a fan or bogen, there will be a requirement for some larger/smaller rectangular cubes and some trapezoidal cubes to complete the patterns, and this is normally stated in the specification so that the supplier can include up to 10% off these 'oddball' cubes.

Finishes

Some of the popular 'finishes' for sedimentary setts are depicted below. Reclaimed sedimentary setts, if they have a discernable finish left on their upper surface, tend to have the picked and punched finishes more commonly associated with igneous-sourced setts - see below.

Back in the days before the bureau-Euro-crats came up with the European Standard BS EN 1342, the old British Standard (BS435:1975 Specification for dressed natural stone kerbs, channels, quadrants and setts) had three simple finishes:

- Fine Picked - also known as 'Bush Hammered'; fairly smooth, good non-slip surface

- Fair Picked - moderately smooth; less worked than fine picked

- Rough Punched - self-explanatory! Roughly hewn with high spots chiselled off

... which was straightforward and easily understood.

Now we have to use...

- Hewn - unworked, commonly referred to as 'cropped'

- Coarse Textured - ± 2mm maximum difference between high points and low spots on surface

- Fine Textured - ± 0.5mm maximum difference between high points and low spots on surface

...confusion sometimes arises because bush-hammering, a popular finish for pedestrian areas, might be coarse or fine textured, as might flame texturing.

The standard also gives prominence to a texture referred to as "Dolly Point" which seems to be some coarse bush-hammer like finish popular in Italy!

Colour

There is a phenomenal range of colours available, virtually any colour you can imagine, but finding it can be quite a task. The problem isn't helped by many suppliers giving delusional names to their offerings. Midnight Glacier probably sounds bloody wonderful to a marketing droid, but doesn't actually tell me what colour the damned stone is.

Even when these aspirational names are rejected, one person's mid-grey is another's dark grey, so colour is always best judged from actual samples.

If you are looking for a particular colour to use on your project, contact the suppliers listed on the links page and ask for details of their colour range - not all suppliers will stock all colours.

Coverage

Coverage rates are quite variable, given the random nature of the stone used for setts and cubes, but for guidance only....

| Type of Stone | Dimensions(L x W x D) | m² perTonne | Single edging (Lin m) | Approx nr per T |

| Granite cubes | 50x50x50mm | 9.0m² | 150m | 2,800 |

| 80x80x80mm | 5.7m² | 63m | 700 | |

| 100x100x100mm | 4.5m² | 40m | 350 | |

| 150x150x150mm | 3.0m² | 18m | 100 | |

| Granite setts | 100x100x50mm | 8.8m² | 75m | 680 |

| 200x75x150mm | 3.9m² | 35m | 165 | |

| 200x150x100mm | 2.9m² | 26m | 120 | |

| 300x100x200mm | 2.0m² | 19m | 62 | |

| Gritstone setts | 150x125x100mm | 4.8m² | 32m | 110 |

| 200x150x150mm | 3.2m² | 19m | 70 | |

| 275x100x200mm | 2.4m² | 20m | 75 |

Patterns

Although it is possible to lay setts and cubes in almost any configuration or design, there are four key patterns that are seen time and time again with sett work in Europe. These are:-

- Coursed

- Random

- Fan

- Bogen

See the Laying Pages for details on different laying techniques.

Coursed

This is without doubt the most popular pattern and much of the 18th and 19th century sett work laid to the streets and squares of towns and cities is laid to this pattern. It's the traditional 'cobbled streets' pattern, with the courses running at 90° to the direction of traffic (transverse), and it often features a longitudinal (running in same direction as traffic flow) channel at each edge, as shown in the photograph opposite.

A coursed pattern is very simple to lay. The newly-quarried and sawn stone sett paving now widely available, is cut to accurate rectangles and is ideally suited to being laid in courses.

Reclaimed setts and hand-hewn materials are much more irregular and so need to be laid to a taut string line to ensure the courses remain parallel and true to level. Coursework looks even better when cambered.

With coursework, it's important that the vertical joints are staggered, whether the setts are new and close-jointed or reclaimed and mortar/pitch jointed.

Different sett widths help to create a more random and natural appearance to the work. New setts are often supplied in standard widths, but a range of widths can be specified if desired. Reclaimed materials often have to be sorted into compatible widths before laying each course, which adds to the labour costs, but makes for a much more visually appealing finish.

Random

Unlike the straight 'rows' of a coursed pattern, a random layout is basically a jumble of stones positioned wherever they will fit. This method of laying was typically used only on low status work, such as industrial yards, stables, haul roads and other places where the presence of a hard surface was far more important than appearance, and/or where the budget was tight. Often, areas paved in a random pattern utilised the poorer quality setts, the rejects and odd sizes from a prestige job nearby or even reclaimed materials that was considered worn.

The same rules for layout creation given on the Random Layouts page apply to setts as well as flags; running joints should be kept to a minimum (around 600-900mm ideally, with setts) and the corners of 4 setts should never meet at a single point. It can be a bit of a brain-teaser working out which stone will fit where, and the end results can look somewhat higgledy-piggledy, especially as the jointing tends to vary between butt-jointed (ie, setts in direct contact with immediate neighbours) to wide joints of 75mm or so. The joint width is a good indicator of the quality of workmanship used to lay the paving - the wider the joints, the poorer the job.

Most random work tends to be a borderline case between setts and cobbles. Just when does a cobble become a sett? How much dressing is required for a field stone or a cobble to qualify as a bone fide sett?

The Kentish Ironstone shown opposite would be teetering on the verge of the cobble/sett boundary, but would probably edge it as a sett by virtue of the rough attempt to create courses from what is a very random stone. In situations like this, it can look fantastic, as long as the jointing doesn't dominate.

European Fan Pattern

This pattern, also known as Belgian pattern or Florentine pattern amongst others, is the most complicated pattern to set out, and only really works with cubes or setts of smaller plan dimensions. However, it is such a visually pleasing layout that it's easy to see just why it has been so popular for so long. It is a frequently used pattern in Europe and is a fairly common choice of pattern for Pattern Imprinted Concrete , although it looks far better in the natural materials than in coloured concrete.

Ideally, it needs a large area to do it full justice, and should be at least 3 metres wide when used as a driveway, otherwise the pattern becomes 'lost'. However, the smaller setts, such as the 100x100mm and smaller units, give excellent results over comparatively small areas. Fans laid with contrasting colours, eg a silver-grey granite and a black basalt, can look stunning when given the space for the pattern and colour to be appreciated.

The idealised setting-out pattern reproduced below can be adapted for most square paving units, including block paving and flags, as well as setts and cubes. If the paving unit is 'n' mm in width, then the radius, r, should equal 10n. This 'rule of thumb' will need tweaking for any given setts as the dimensional accuracy, size range and scale of fan will all affect how 'tidy' the completed fan looks when laid and jointed.

In practice, a number of wedge-shaped or trapezoidal setts are needed to prevent the joints becoming too wide, and a professional sett layer will usually rough-out a serviceable fan before preparing a template from which to work.

Bogens

It's worth noting that there is often some confusion in Britain and Ireland regarding these "arc" patterns. The layout shown above is a fan: there are a number of repeating 'shapes' that interlock and cover a larger area. However, on the continent, one of the more popular layouts is the bogen also known as a segmental arc or even radial-sett paving , which is often mistaken for a fan but is actually a series of stacked arcs. Bogen layout is complex and requires the skills of an experienced artisan as the setts at the ends of the arcs, where one arc meets its neighbour, need to be somewhat smaller than those in the centre of each arc.

Traditionally, bogens are incredibly strong layouts as the arcs work to dissipate forces over a much larger area. Their development and use reached a peak when horse-drawn traffic dominated the streets, but since the advent of modern vehicles, their use has been gradually demoted to one of aesthetics. However, they remain popular in continental Europe and there has been a sign of renewed interest in both Britain and Ireland since the price and availability of imported granite setts became more favourable in the early years of the 21st century.

Pros and Cons

The 'domed' surface of the "Hovis-loaf" type reclaimed setts can be awkward to walk on, especially in high-heeled shoes (or so I'm told!)

The irregular nature of the surface can also make access difficult for hand-pushed garden tools such as non-pneumatic tyre wheelbarrows, and lawnmowers. Even relatively flat-topped setts can be difficult to traverse if the jointing is recessed, but the newer sawn setts have wonderfully smooth and level faces, and being laid butt-jointed as is concrete block paving, they present no hazard whatsoever, regardless of which footwear one is wearing.

Properly constructed sett paving is more or less completely impermeable and therefore must be adequately drained to gullies or other suitable drainage points .

Once complete, it should require no maintenance other than the occasional sweep with a broom to remove accumulated dust, etc. Some of the imported sandstone setts can be something of an algae-magnet, so regular cleaning may be required or it may be considered worthwhile to treat them with a suitable sealant .

Relatively expensive - good work costs good money. There are plenty of chancers who claim they can lay setts and then proceed to bollix the job because they simply do not have the relevant experience, and it's that experience that costs. While the setts themselves can be found from £30 per square metre (and upwards) a top-class streetmason or sett-layer will often charge £40-£6per m² to lay them.

When laid well, or when laid to a fan pattern, they can look stunning. All too often the reclaimed or hand-hewn setts are laid slap-dash and then have plain 'white' mortar slapped all over them as an attempt at pointing.

Time consuming and labour intensive....not to be undertaken by the faint hearted.

If you are employing a paving company to lay reclaimed or hand-hewn setts for you, insist on seeing some previous work in the same materials; the skills required in laying irregular setts are not the same skills used with block paving or the regular-dimensioned sawn setts.

For an easier and cheaper alternative to cobbles and setts, take a look at some of the concrete sett blocks now available from the top manufacturers and described more fully in the relevant section of this site. There is a wide range available, including flat, tumbled blocks, domed-top blocks, textured surface blocks and some pretty disgusting and unconvincing 'copies'. As all these blocks can be screed bedded and sand jointed, the labour rate is significantly reduced and therefore they are considerably cheaper than either reclaimed or new stone.

Buying Advice

Setts can be quite expensive, especially the 'newly quarried' stones, although the new, thinner setts specifically sawn for residential projects do help keep the cost to an acceptable level. Prices for new materials range between £30 and £180 per square metre, depending on thickness, type of stone, finish and quantity.

Reclaimed ("second-hand") granite setts can command a price of £120-250 per tonne (equivalent to around £30-65 per square metre), while gritstone setts are cheaper, starting at around £40 per tonne (£12.50 per m²) for uncleaned, unsorted low-grade stuff. The price for reclaimed materials is highly variable, with significantly higher prices being charged in the SE of England.

There is massive variation in prices charged for the actual laying of sett work. Some of this is because of the wide range of prices quoted for different materials, and some is because of the high level of workmanship required to achieve the best results.

Close-jointed new sett work is much quicker to lay and consequently costs less in labour per unit area than the individually laid hewn setts or cubes, which take almost as long to joint and seal as they do to lay. See the sett construction page for more information.

Buy by area or buy by weight?

Most suppliers sell by weight, not by area, relying on the professionals to know what typical coverage is achieved per tonne of various different sett types. This method of buying/selling is preferred because weight is indisputable - an alleged tonne of setts either weighs a tonne or it doesn't, and it's easy to check, whereas selling by area is vague and open to abuse.

A trader can't possibly know what joint width any given sett-layer will achieve. It's all well and good them saying that with a 10mm joint this lot/bag/crate of setts will cover 10m², but joint width will vary, from the ankle-snapping (like that truly bloody awful installation on Coronation Street - must be at least 25mm between each sett – the jointing mortar supplier must have loved that job!) to the 'fag-paper' width joints where adjacent setts are actually touching.

I would never buy from a trader selling setts by area. My attitude is that such an arrangement is set up to deceive. What's to stop some charlatan selling 9 setts as capable of covering a square metre, which they possibly would if they were laid with 300mm wide joints?

In theory, 43 setts at 200x100mm should just about cover a square metre allowing for 10mm joints, but that makes no allowance for wastage, and there’s nearly always one or two plug-ugly setts in every barrowful. Then, if the joint width was reduced to, say, 6mm, just 4mm narrower, then roughly 46 setts are required for each m². And with close jointing (1-3mm) that goes up to 49 setts short for every m².

The coverage table above gives a reliable guide to the expected coverage for various popular types of setts but be aware that wastage AND joint width will have an impact on just what sort of coverage is actually achieved on any particular project.

The professional sett layer buys by weight, relying on experience to know what sort of coverage figure to expect for a given pattern and style of laying, and making an educated allowance for wastage (often around 5%).

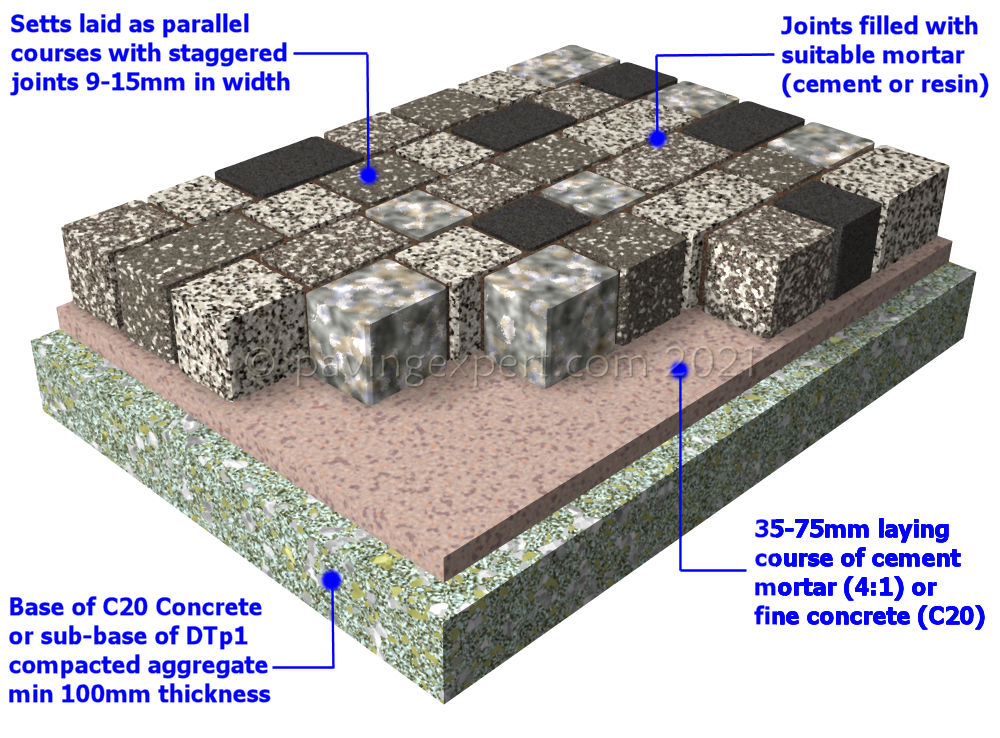

Construction Diagram

See the Laying Setts page for fuller construction details